Growing up as a queer Asian American meant living multiple lives. To my grandparents back in China, I was studious, fluent in Mandarin, piano prodigy by night, and respectful member of society by day. To my white friends, I loved Pacsun, The Killers, and hid my love of stinky tofu and preserved duck eggs. But the most impactful life I lived was with my parents, who I somehow managed to convince that I had a crush on the Lisa I took to prom (who I’m actually great friends with now); and that, of course, I was going to become a doctor.

When I reflect on the intersectionality of my queer and Asian-American identities, I think back on how ferociously these two identities clashed, but ultimately how it’s provided me an incredible point of view, lessons in resilience, and continues to highlight a need for queer Asian representation in media and positions of influence.

Coming out is a unique journey for everyone, and for me, it was made more complicated by the sacrifices that mom and dad selflessly made to give me opportunities that came with a Western upbringing.

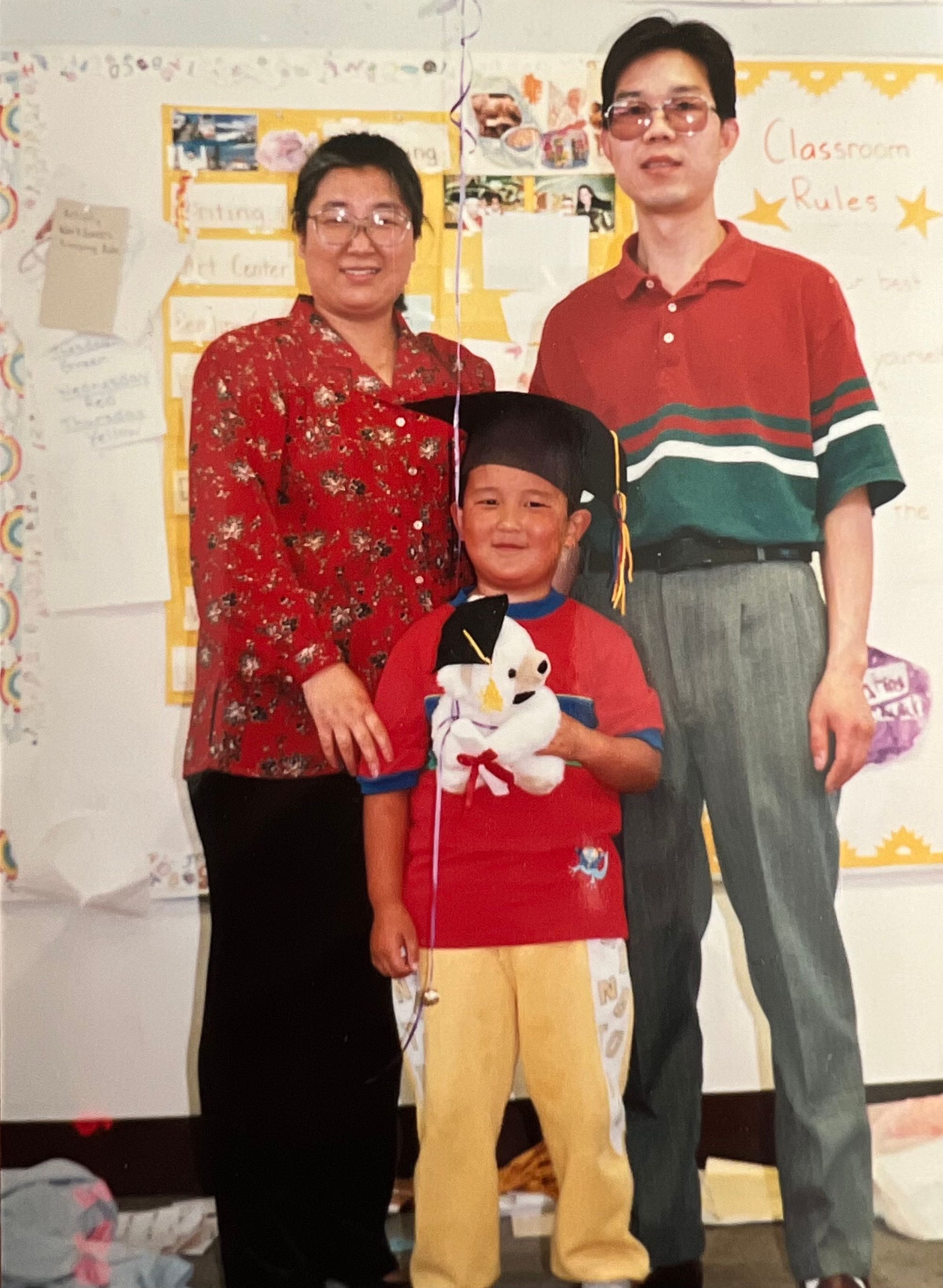

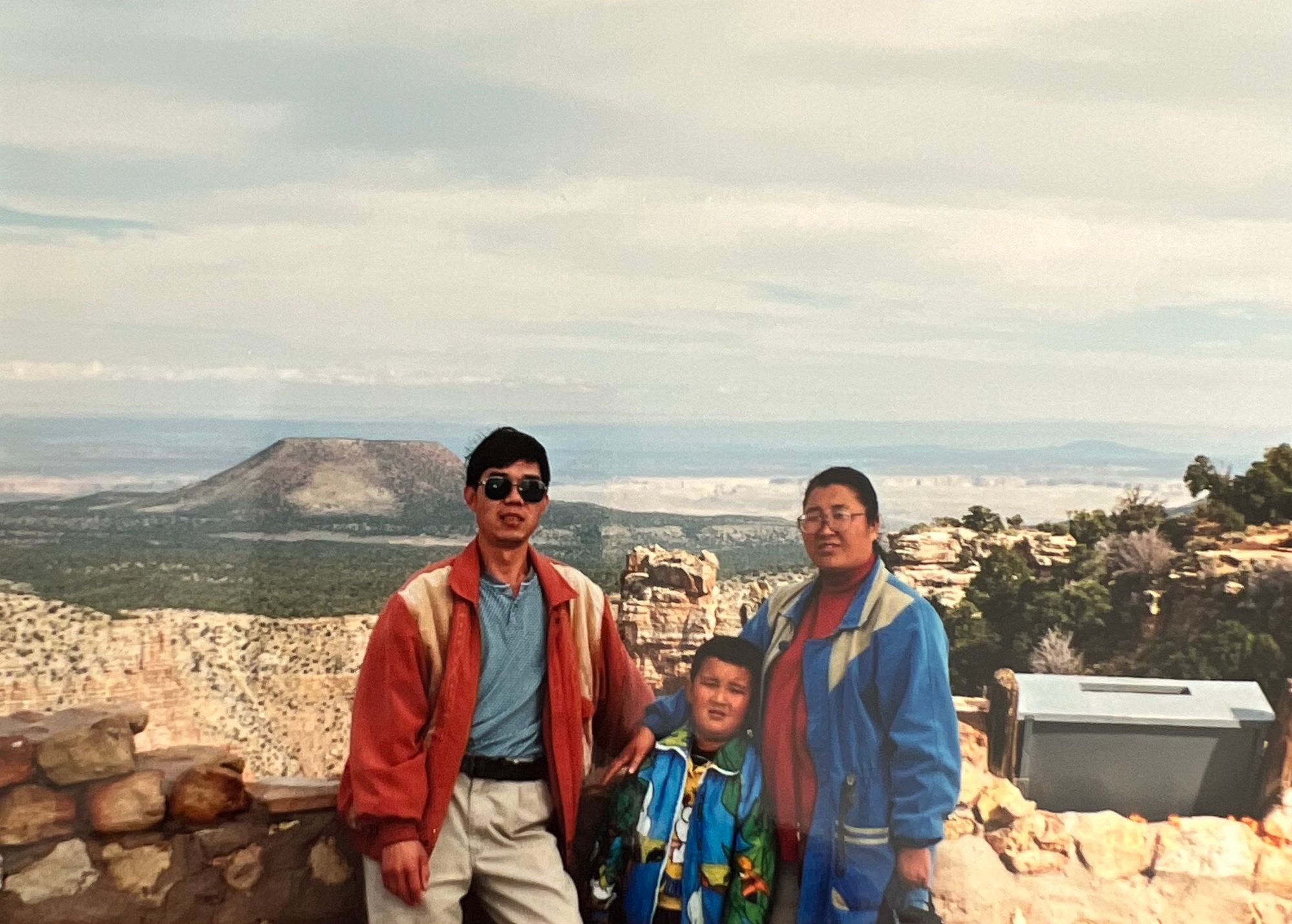

A bit of backstory: in 1993, right after I was born, my mom was a doctor and my dad a civil engineer in Taiyuan, a large city in the Shangxi province. They were happy––surrounded by friends from school, lived close to their relatives, and made a comfortable salary. However, my mom, the force of nature that she is, read about a scholarship opportunity in North America in partnership with Taiyuan’s medical school. Without any hesitation, she applied, was subsequently accepted, and convinced my dad to hop on a flight to San Francisco with a 2-year old in tow.

Overnight, mom and dad went from living medium-large in a community where everyone understood them, to a 400 sq ft apartment by University of California, San Francisco––a foreign place with a foreign language. Mom spent the next few years learning as much English as she could, while simultaneously doing cutting-edge medical research and fending off xenophobic microagressions. Dad found a job as a dishwasher, and then a line cook at a Chinese restaurant in the Portola district of San Francisco.

They were thousands of miles away from the closest family member at a time when calls home were 39 cents per minute, and they did everything they could to survive and give me a happy upbringing on a scholar and line cook’s salary. Even as we shopped the discount aisle at the neighborhood grocery store (shoutout to 23rd and Irving grocery), they somehow always found room in the budget for my private piano lessons and even a gameboy for my 7th birthday.

The amount they sacrificed to enroll me in good schools, maximize my opportunities, and even get me a sibling (China had a one child policy back then) became a source of personal pride for me––but also one of guilt. Mom and dad had worked damn hard to get us to where we were, and my biggest fear was to disappoint them in any shape or form. I wanted to live up to their expectations, but their expectations included hopes that I could not deliver on: marry a lovely woman and build a beautiful family worthy of the sacrifice they made. I was immensely scared to come out to them and be a let-down, so I spent my entire teenage years flipping between the different stages of gay grief.

I came out to my mom by accident. The force of nature she is, my mother had a habit of making sure that I wasn’t up to any trouble. She’s also extremely perceptive, so when the same phone number kept appearing on our phone bill (I was quite the fan of late night calls with my secret boyfriend), she sleuthed out that I had a boyfriend. Quite the emotional conversation followed, which cycled through her wondering if she did anything wrong, to repeatedly asking if I was sure about my sexuality. We left that conversation in 2009 with a very big hug but a lot of uncertainty. She clearly was struggling with the idea of a gay son, but I could tell that she was doing everything she could to work through her feelings and keep our relationship intact.

Since that six hour-long conversation a decade ago, my mom slowly became my closest friend and confidant, even helping curate photos for my Hinge profile. I moved back home after college, and after crying it out on mom’s shoulder after a horrible breakup, we slowly found it much easier to open up and share.

I later found out that she had made an intentional effort at the hospital to engage with her queer colleagues and learn their stories; she read a lot of books and searched for role models. In particular, she had met and gone to lunch multiple times with the vice-chair of the radiology department, a queer and Asian man. She saw firsthand a successful, respected Asian man living his life out and proudly, and learned about how he struggled with his parents. She met a trans Asian lawyer in one of her clinical studies, and heard firsthand about how they left a big law job to join a legal clinic to help immigrants navigate the green card process. With every story, she came to realize that queer Asians not only existed, but thrived and had monumental impacts on their families and communities.

I came out to my dad about six months ago, while getting ready to propose to my partner. I’ll be honest, it didn’t go as I’d hoped. My partner and my dad had actually met each other a few times in the past year (we own a bar and it quickly became a family project), but never in the capacity as my romantic partner. I had hoped that my dad had figured it out on his own, but the news was delivered with quite a bit of shock. It was a difficult (and also very long) conversation that was reminiscent of the chat I had with mom a decade ago. Dad was clearly struggling with the concept, but still trying to put family first. But this time, I had mom in my corner, sharing how long it took her to come to terms with my sexuality, the stories she heard over the course of the past decade, and how everything was going to be okay. Months later, at a hot pot restaurant for my dad’s 61st birthday, as he pulled out Google on his phone to find the score of the Warriors / Kings game, I saw that one of his most recent searches was “gay Chinese CEO.”

I share this story during AAPI month for 2 important reasons.

The first: there are so many privileges and learnings unique to growing up as an Asian-American immigrant, most notably the undying devotion to family and resilience that often leads to well-being. But married to these privileges comes a unique set of challenges to the AAPI queer community: the pressure of upholding family tradition, the reluctance to let our parents down, the difficulties in having tough conversations, and ultimately, the complex journey to acceptance. Highlighting these stories helps build allies and empathy in the fight against racial bias and hate, within the LGBT community and beyond.

The second: we need louder and more ample representation of queer asian leaders in media, business, and all other sectors of society. My mom’s path to acceptance, and what I hope my dad’s path will be, centered around humanizing and learning from queer AAPI leaders. While these role models serve as inspiration to queer Asian-Americans, they are additionally instrumental in proving to our families that success is possible (and probable!) for those in our community. The prominence of these leaders make less foreign the idea that a gay, asian man, born to immigrant parents, can achieve amazing things to make his family proud.

I hope that months or years from now, an asian mom or dad that learned their kid is gay will Google “gay asian CEO” and my name and this story will come up. We want nothing more than to make our parents proud and honor the sacrifices that they’ve made to get us to this place, and want them to know that we can, and will, be successful. We will be successful not despite our identities, but because of them and the resilience we’ve built from this unique part of our lives.